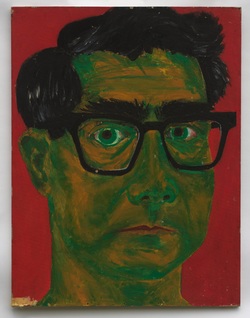

Next Sunday is kind of a big deal at my house. I’m hosting an art show, my deceased father’s first so far as I know. If he were still alive, he would be 97. His paintings and ceramics have always graced different family members’ homes but never before has so much Joe Rice art been gathered in one place for the express purpose of sharing it with a broader audience.

I’ve spent the week clearing my home of photographs, memorabilia, non-Joe Rice art and extraneous furniture, preparing the main rooms where the “show” will be, a circle leading from foyer to front room, dining room, hallway, living room, into the kitchen, through another hall and then looping back to the foyer. My hope is to replicate, as much as possible, a gallery-like experience where the focus is squarely on the art, my father’s art.

I’ve spent the week clearing my home of photographs, memorabilia, non-Joe Rice art and extraneous furniture, preparing the main rooms where the “show” will be, a circle leading from foyer to front room, dining room, hallway, living room, into the kitchen, through another hall and then looping back to the foyer. My hope is to replicate, as much as possible, a gallery-like experience where the focus is squarely on the art, my father’s art.

There are factors that render my home less than ideal for an art show. Poor lighting, irregularly shaped rooms, windows and wide entryways that chop up much of the available wall space. But there are pluses too. The art will never leave family hands. Opportunities for damage, loss, even theft, are minimized. It’s a baby step and that feels appropriate for a first foray.

I emptied the dining room china cabinet and filled its lighted glass shelves with Joe Rice ceramics and odd bits of his jewelry. Some of the jewelry is mounted on cloth-covered frames. The paintings are arrayed by style or period and also color palette. The larger canvasses fill the tall foyer or are placed in locations where viewers can attain enough distance to appreciate perspective and scale. Smaller pieces and ones that demand closer inspection line the halls and narrower spaces. Each room has at least one signature piece, what I consider the show’s “stars.”

I’ve never done anything like this before.

As the day approaches, my anxiety grows. Sleep is interrupted. Diet is shot to hell. I worry how people will respond to the art and whether they will consider the exhibit time well spent. I wonder if there is enough art on display, whether I’ve chosen the right pieces and if my efforts appear amateurish, which I realize they inevitably must, for I am an amateur.

I speculate what my father would make of all this. He was a private man. He had opportunities to exhibit his work in coffee houses and galleries during his lifetime, as well as offers to buy. He chose not to. Would this current endeavor offend his sensibilities? If he were alive, would he say I have no right, that I have crossed the line?

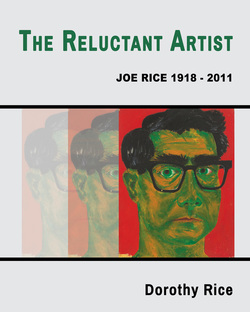

But then I’ve already crossed a line, probably several lines. I published a book about him. It’s out there in the universe—in a modest way to be sure, a book from a small press about an unknown artist, by an unknown author. Yet it is out there nonetheless.

As my hairdresser said to me this afternoon, “this book is a good thing, Dorothy.” On my last visit to the salon I’d given her a copy and was touched by the details she recalled. “The next generations, they forget about all these things," she said. "When we are gone, no one remembers.”

I emptied the dining room china cabinet and filled its lighted glass shelves with Joe Rice ceramics and odd bits of his jewelry. Some of the jewelry is mounted on cloth-covered frames. The paintings are arrayed by style or period and also color palette. The larger canvasses fill the tall foyer or are placed in locations where viewers can attain enough distance to appreciate perspective and scale. Smaller pieces and ones that demand closer inspection line the halls and narrower spaces. Each room has at least one signature piece, what I consider the show’s “stars.”

I’ve never done anything like this before.

As the day approaches, my anxiety grows. Sleep is interrupted. Diet is shot to hell. I worry how people will respond to the art and whether they will consider the exhibit time well spent. I wonder if there is enough art on display, whether I’ve chosen the right pieces and if my efforts appear amateurish, which I realize they inevitably must, for I am an amateur.

I speculate what my father would make of all this. He was a private man. He had opportunities to exhibit his work in coffee houses and galleries during his lifetime, as well as offers to buy. He chose not to. Would this current endeavor offend his sensibilities? If he were alive, would he say I have no right, that I have crossed the line?

But then I’ve already crossed a line, probably several lines. I published a book about him. It’s out there in the universe—in a modest way to be sure, a book from a small press about an unknown artist, by an unknown author. Yet it is out there nonetheless.

As my hairdresser said to me this afternoon, “this book is a good thing, Dorothy.” On my last visit to the salon I’d given her a copy and was touched by the details she recalled. “The next generations, they forget about all these things," she said. "When we are gone, no one remembers.”

If nothing else, there is that—a book to hold, a website to discover, an art show as celebration and homage. I don’t know what, if anything, comes next for this collection of objects, artifacts of my father’s life. My hope is that the art—at least a handful of these images I have always found so iconic, so resonant—assumes a life of its own, apart from my efforts.

It is the eve of my father’s first art show, something he would never have conceived and perhaps not have condoned, though I like to think that there was pride beneath his modesty and that he might be secretly pleased. I feel jittery with anticipation, as if these works were of my own creation, perhaps more so. I feel responsible. I got it into my head in the years before he died to catalog his work and create some kind of record. That part he knew about. It is now nearly ten years later.

I did it for you Dad, whether you wanted me to or not. I did it for our family. And I did it for myself—perhaps imagining that whatever kept you creating art all those years would rub off on me, would attach by association and heredity.

It is the eve of my father’s first art show, something he would never have conceived and perhaps not have condoned, though I like to think that there was pride beneath his modesty and that he might be secretly pleased. I feel jittery with anticipation, as if these works were of my own creation, perhaps more so. I feel responsible. I got it into my head in the years before he died to catalog his work and create some kind of record. That part he knew about. It is now nearly ten years later.

I did it for you Dad, whether you wanted me to or not. I did it for our family. And I did it for myself—perhaps imagining that whatever kept you creating art all those years would rub off on me, would attach by association and heredity.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed