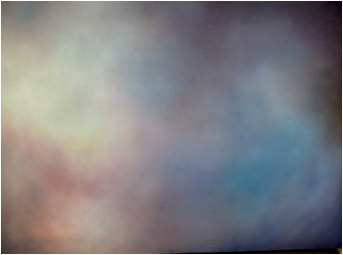

My father’s final paintings verged further and further into pure abstraction. There are a dozen fuzzed atmospheric blurs that evoke outer space and shapes so muted and indistinct they might be nothing at all. I never asked, but I’ve always imagined these were his final efforts to work within the confines of his physical limitations, to keep painting as long as he could. |

One day last week my daughter and I went for an early morning walk. It wasn't yet 6 when we set out, bundled in coats and hats against the February chill. After a night of wind and rain, there was only the slightest hint of light in a dark and stormy sky, just enough that it wasn't full dark as we left the house and walked fast to warm ourselves, her arms swinging, my hands thrust deep in the pockets of a quilted jacket.

I lost sight of my daughter as she began to jog. The minutes mounted as I trod the quiet sidewalk, interrupted by the occasional flash of headlights bobbing towards me or the shadow of another silent walker on the other side of the street. Morning light grew by imperceptible degrees. It pushed through the dark such that weak sunlight backlit the dense, swirling cloud cover, revealing patterns of lighter gray and shades of blue against the black.

Shapes and shadows emerged from the obscurity as dawn broke through the night. The sky began to make sense again, to be recognizable. My mind wandered to a stack of my father's paintings that rested against the wall in the foyer, near the front door, four shapeless, formless atmospheric blurs in muddied blends of misty color.

I lost sight of my daughter as she began to jog. The minutes mounted as I trod the quiet sidewalk, interrupted by the occasional flash of headlights bobbing towards me or the shadow of another silent walker on the other side of the street. Morning light grew by imperceptible degrees. It pushed through the dark such that weak sunlight backlit the dense, swirling cloud cover, revealing patterns of lighter gray and shades of blue against the black.

Shapes and shadows emerged from the obscurity as dawn broke through the night. The sky began to make sense again, to be recognizable. My mind wandered to a stack of my father's paintings that rested against the wall in the foyer, near the front door, four shapeless, formless atmospheric blurs in muddied blends of misty color.

“The world is full of magic things, patiently waiting for our senses to grow sharper.”

― W.B. Yeats

I'd retrieved the paintings from my sister's garage on the weekend, thinking to store them in the upstairs closet, where I reasoned they would be better protected from the extremes of another Sacramento summer. I hadn't considered hanging them in the house. Nor had I thought to include them in the art show I'd recently held, a retrospective of fifty years of father's art, spanning the 1950s through the early 2000s. In my mind, these paintings, some of his last, paled in comparison to the bold, crisp compositions of earlier decades. I'd always found them sad and disappointing, a reminder of what my father was no longer capable of.

As I walked I kept an eye to that early morning sky and wondered if this was what my father had been trying to convey or depict with his blurry canvasses.

I didn't move the paintings into the upstairs closet. That morning, after my daughter had left for school, I hung three of the four, one above the tall front door, another over the mantle in the living room and a third at the top of the stairs.

As I walked I kept an eye to that early morning sky and wondered if this was what my father had been trying to convey or depict with his blurry canvasses.

I didn't move the paintings into the upstairs closet. That morning, after my daughter had left for school, I hung three of the four, one above the tall front door, another over the mantle in the living room and a third at the top of the stairs.

When my sister came to visit I showed them to her.

"I like them now," I said, a little embarrassed to admit it. "Is it just that they're Dad's?"

"It could be art glare," she said, with a shrug.

I knew what she meant. We'd talked about it before. How we treat our father's every sketch and painting as if it were a masterpiece. We have no objectivity. Our feelings for our father bias our perspective. There is too much glare. I suppose everyone is subject to glare to one degree or another as an inevitable consequence of having lived a particular life.

Which is not to say that the art isn't great, only that my sisters and I are not the ones to judge.

For now these representations of stormy skies, dawn's first light, outer space or perhaps something more ethereal, hang in my home. Where I once perceived only unskilled abstractions, I now see intention and purpose. I see artistry and vision.

I'll never know what these blurred images were to my father, or even which side of the canvas is up. I can only know what they are to me, how they make me feel and what they make me think.

"I like them now," I said, a little embarrassed to admit it. "Is it just that they're Dad's?"

"It could be art glare," she said, with a shrug.

I knew what she meant. We'd talked about it before. How we treat our father's every sketch and painting as if it were a masterpiece. We have no objectivity. Our feelings for our father bias our perspective. There is too much glare. I suppose everyone is subject to glare to one degree or another as an inevitable consequence of having lived a particular life.

Which is not to say that the art isn't great, only that my sisters and I are not the ones to judge.

For now these representations of stormy skies, dawn's first light, outer space or perhaps something more ethereal, hang in my home. Where I once perceived only unskilled abstractions, I now see intention and purpose. I see artistry and vision.

I'll never know what these blurred images were to my father, or even which side of the canvas is up. I can only know what they are to me, how they make me feel and what they make me think.

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro' narrow chinks of his cavern.”

― William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

RSS Feed

RSS Feed