Roxanne, my older sister by four years, remembers a set of Eames chairs and a matching table from our childhood, when we lived on 45th Avenue in San Francisco’s Sunset District during the 50s and 60s, two blocks from the zoo, and the Doggie Diner. She says the chairs were orange, with molded bucket seats. She can picture Dad, standing behind her at the dining table, leaning over the back of the orange chair to tap the shell on her soft-boiled egg with the back of a spoon.

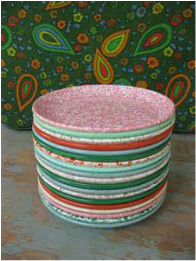

My younger sister Juliet doesn’t remember the orange, plastic chairs. Instead she recalls a set of salmon-colored speckled dishes, and eating her morning oatmeal from one of the bowls.

My younger sister Juliet doesn’t remember the orange, plastic chairs. Instead she recalls a set of salmon-colored speckled dishes, and eating her morning oatmeal from one of the bowls.

Roxanne was reminded of the Eames chairs while buying new chairs for her condo, reproductions of the original iconic designs of the husband and wife team Charles and Ray Eames. As she described them to me, and then sent me photos on her phone, I thought of the Jetsens cartoon, their futuristic house, the dad’s scooped out recliner, daughter Judy zooming to Orbit High School in a bubble-like plastic space pod. But for my sister the chairs evoked something else, a particular sense of style, a hip sensibility born of our parents’ Berkeley bohemian days and Dad being a modern artist with a distinct eye for clean lines. She recalls the furnishings in our home as being spare, with father’s art on the walls, the space age chairs, and the coffee table and side tables Dad built down in the basement.

The tables Dad made, which Roxanne still has, are of polished hardwood, with softly rounded corners and sleek, thin legs. The coffee table has a nifty recessed receptacle for magazines and papers; now, over fifty years old, the table looks right at home between the retro plastic chairs, with one of father's glazed pottery lamps on top.

The tables Dad made, which Roxanne still has, are of polished hardwood, with softly rounded corners and sleek, thin legs. The coffee table has a nifty recessed receptacle for magazines and papers; now, over fifty years old, the table looks right at home between the retro plastic chairs, with one of father's glazed pottery lamps on top.

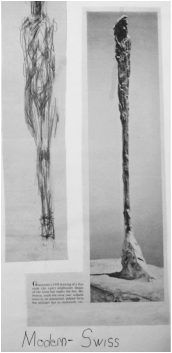

| I remember a tall, slender statue Dad made, dark polished wood with smoothed-out oval openings up its length. It narrowed towards the top, like a spire. Strands of crosshatched silver filled the windows in the wood, like filigree shutters. In my mind, the wooden spike is reminiscent of both the jewelry father fashioned in the 50s (also wood and silver) and the work of Alberto Giacometti. It's possible my father never made any such thing and I'm only lumping images together, yet I can picture it quite clearly. When I was in the 5th or 6th grade, my father helped me with a school report on the history of sculpture. We sat on the living room couch, beneath the bay window that opened onto 45th avenue, turning the pages of art books and magazines. There was an article in Life Magazine about Giacometti with photos of his elongated, molten metal human figures. “What do you think?” my father asked. By the way he paused to touch the photos, I could tell he liked this guy. So I did too. I still have that grammar school report, an oversized, cumbersome thing with a heavy cardboard cover and a dozen magazine photographs pasted on thick sheets of paper. The text don't really sound like something I would have written at that age. I can hear my father, dictating to me as I formed my rounded letters. "The French sculptor Rodin was the first to break away from the dead past. He did not try to imitate life. He liked to distort and find new ways of doing things. Even his subjects were shocking for his time, as seen in his statue "The Kiss." |

I don’t remember the molded plastic chairs, soft-boiled eggs or salmon-colored breakfast bowls. But I love that my sisters do. As for my own memories, particularly of childhood, I sometimes question what I actually remember and what I have cobbled together from bits and pieces of actual memory, bolstered by photographs, museum visits and snippets of conversation, all mashed together in ways that feel like something that could be real, that could have happened.

Though they weren't my memories, the stylish chairs and the speckled Melamine bowls are now in my head too, adding more detail, color and texture to the movie set that is my childhood home. I believe in them though I don’t actually remember them. Our collective memories form a sort of Venn diagram. The circles of our distinct memories overlap. Over time, the common area grows. Perhaps we forget who added which details to the picture. It ceases to matter. I imagine my sisters and I want to remember that place of our childhood, to recreate it as a whole intact universe that will last forever, if only in our minds.

We cling to the few physical artifacts. The paintings, tables, dishes, and the rest, have become treasured relics.

“Do you have any of those plates?” Juliet asks me on the phone, with a hopeful note in her voice.

“Do you know where the other end table is?” asks Roxanne. “And where’s that portfolio of sketches,” she says. “We should go through it again. Do you think there are any drawings of furniture?”

I don’t think there are. Nonetheless we will haul it out from beneath the bed to flip through the weathered sheaf of sketches once again, searching for more clues, more remnants of the touchable past.

Though they weren't my memories, the stylish chairs and the speckled Melamine bowls are now in my head too, adding more detail, color and texture to the movie set that is my childhood home. I believe in them though I don’t actually remember them. Our collective memories form a sort of Venn diagram. The circles of our distinct memories overlap. Over time, the common area grows. Perhaps we forget who added which details to the picture. It ceases to matter. I imagine my sisters and I want to remember that place of our childhood, to recreate it as a whole intact universe that will last forever, if only in our minds.

We cling to the few physical artifacts. The paintings, tables, dishes, and the rest, have become treasured relics.

“Do you have any of those plates?” Juliet asks me on the phone, with a hopeful note in her voice.

“Do you know where the other end table is?” asks Roxanne. “And where’s that portfolio of sketches,” she says. “We should go through it again. Do you think there are any drawings of furniture?”

I don’t think there are. Nonetheless we will haul it out from beneath the bed to flip through the weathered sheaf of sketches once again, searching for more clues, more remnants of the touchable past.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed