I had no expectations for the craft fair at the Elks Lodge near my home in suburban Sacramento. None.

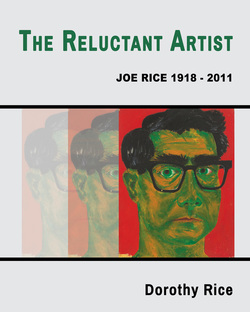

I'd been put on a waiting list and my check had been returned weeks prior. With a dozen names before mine, I'd put it out of my mind, assumed it wasn't happening this year, if ever. It had been a long shot notion to begin with. Who would want to buy my art book/memoir about my dad when they could buy fudge and peanut brittle, hand made ornaments, jewelry, aluminum foil Xmas trees and quilted pot holders - and for so much less!

When I got the phone call the night before and was asked, "Did I still want a half table?" I had no time to think of a reason not to, so I said, "Sure."

The fair was what I'd expected in most respects. Venders and customers with an average age of 60, if not 70 - myself included. As many walkers, canes and pastel perms per capita as at my mother's memory care facility. Tables laden with hand crafted soaps and lotions. Nut breads and candies. Anything and everything that can conceivably be fashioned with yarn, felt, fabric squares and plastic beads. One new, and sobering, item - adult bibs.

My neighbor, another last minute substitution like me, was a Kenyan woman selling very cool bracelets, key chains and necklaces. Our shared table was near the food "concession," several long tables covered with an assortment of homemade cookies, bars, brownies, cakes and pies. I cruised by before the doors opened to the public and contemplated what to purchase for a mid-morning break.

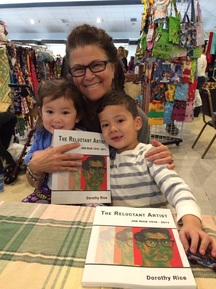

I set up my table - a green and gold tablecloth, giveaway art cards and book marks, a few copies of the book, a candy basket, some old photos and a couple of Dad's ceramic pieces. I pasted on my best smile and determined to make the most of the morning and afternoon, no matter what did, or didn't, transpire.

I'd been put on a waiting list and my check had been returned weeks prior. With a dozen names before mine, I'd put it out of my mind, assumed it wasn't happening this year, if ever. It had been a long shot notion to begin with. Who would want to buy my art book/memoir about my dad when they could buy fudge and peanut brittle, hand made ornaments, jewelry, aluminum foil Xmas trees and quilted pot holders - and for so much less!

When I got the phone call the night before and was asked, "Did I still want a half table?" I had no time to think of a reason not to, so I said, "Sure."

The fair was what I'd expected in most respects. Venders and customers with an average age of 60, if not 70 - myself included. As many walkers, canes and pastel perms per capita as at my mother's memory care facility. Tables laden with hand crafted soaps and lotions. Nut breads and candies. Anything and everything that can conceivably be fashioned with yarn, felt, fabric squares and plastic beads. One new, and sobering, item - adult bibs.

My neighbor, another last minute substitution like me, was a Kenyan woman selling very cool bracelets, key chains and necklaces. Our shared table was near the food "concession," several long tables covered with an assortment of homemade cookies, bars, brownies, cakes and pies. I cruised by before the doors opened to the public and contemplated what to purchase for a mid-morning break.

I set up my table - a green and gold tablecloth, giveaway art cards and book marks, a few copies of the book, a candy basket, some old photos and a couple of Dad's ceramic pieces. I pasted on my best smile and determined to make the most of the morning and afternoon, no matter what did, or didn't, transpire.

What happened was, in many respects, magical.

I sold a handful of books, but that wasn't what made the magic. It was moments like these:

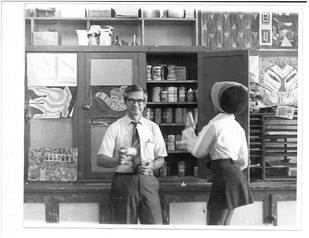

The art teacher who said she was inspired by my father's story, by his 30 years teaching art in the San Francisco public schools. We talked for 15 minutes about the state of art education, about the power of creativity, about kids.

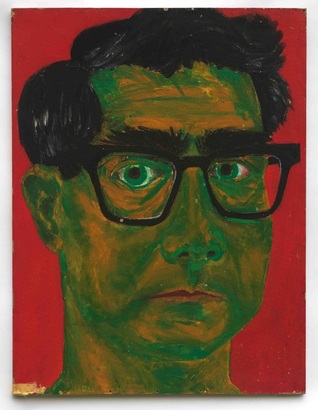

A visit from my sister and from my daughter-in-law - who brought my grandchildren, her mother and sister. My grandson played with the art cards. "These are at my house," he said, picking up two of the cards, the one of the green self-portrait of my father (the book's cover illustration) and the giant acorn squash in a room that's an homage to Magritte's iconic green apple.

The old friend who sat with me for most of the day - a natural saleswoman as it turns out - who spelled me for bathroom breaks and brought me coffee and croissants from the French bakery across the intersection.

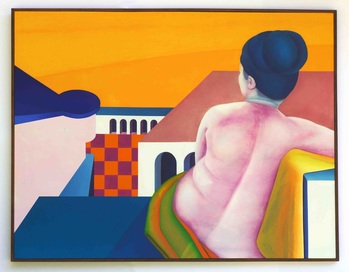

The woman who stood at my table turning the pages of the display copy of my book, exclaiming at the colors, the images, pausing at the ones she loved.

"This inspires me so much," she said. "I used to paint. I want to begin again when I retire. I came here today hoping to find something special, something I couldn't find anywhere else, and I did."

I sold a handful of books, but that wasn't what made the magic. It was moments like these:

The art teacher who said she was inspired by my father's story, by his 30 years teaching art in the San Francisco public schools. We talked for 15 minutes about the state of art education, about the power of creativity, about kids.

A visit from my sister and from my daughter-in-law - who brought my grandchildren, her mother and sister. My grandson played with the art cards. "These are at my house," he said, picking up two of the cards, the one of the green self-portrait of my father (the book's cover illustration) and the giant acorn squash in a room that's an homage to Magritte's iconic green apple.

The old friend who sat with me for most of the day - a natural saleswoman as it turns out - who spelled me for bathroom breaks and brought me coffee and croissants from the French bakery across the intersection.

The woman who stood at my table turning the pages of the display copy of my book, exclaiming at the colors, the images, pausing at the ones she loved.

"This inspires me so much," she said. "I used to paint. I want to begin again when I retire. I came here today hoping to find something special, something I couldn't find anywhere else, and I did."

The woman who admired the photograph of my father's family - his Chinese mother and Hungarian father, taken in Manila around 1919. Like my grandmother, her grandparents had found their way from China to San Francisco.

"My grandmother ran a little garment factory," she said.

"Mine worked in one," I said, "sewing underwear."

We compared dates and wondered if it was possible our grandmothers had known one another.

"There is so much amazing history to be found in old photographs," she said.

The diminutive Asian women who gripped the display copy of the book and turned every last page, scrutinizing the photos and asking questions. She came to the series of photographs of Dad's ceramics and looked up at my display.

"Is that the original?" she asked, pointing at the whimsical rhino on the tabletop. "Can I touch him? Can I hold him?" She lifted the statue with both hands and cradled it to her chest as if it were a newborn child. She stroked the shiny glaze and patted its flanks.

"So sturdy," she said. "Don't you ever give this away, or sell it. This is a true treasure, an heirloom."

"My grandmother ran a little garment factory," she said.

"Mine worked in one," I said, "sewing underwear."

We compared dates and wondered if it was possible our grandmothers had known one another.

"There is so much amazing history to be found in old photographs," she said.

The diminutive Asian women who gripped the display copy of the book and turned every last page, scrutinizing the photos and asking questions. She came to the series of photographs of Dad's ceramics and looked up at my display.

"Is that the original?" she asked, pointing at the whimsical rhino on the tabletop. "Can I touch him? Can I hold him?" She lifted the statue with both hands and cradled it to her chest as if it were a newborn child. She stroked the shiny glaze and patted its flanks.

"So sturdy," she said. "Don't you ever give this away, or sell it. This is a true treasure, an heirloom."

I promised her I wouldn't. She didn't buy the book. But the half hour of enjoyment, of connection, she received from it, were palpable.

Dozens were drawn in by the photograph of my father's family. The one where he's an infant, seated on his mother's lap.

"That could be my family," one woman said, with a wistful smile.

There were questions about his heritage. About how his Hungarian soldier father and Chinese mother met.

"So many of us come from somewhere else, don't we?" one woman said.

"Almost all of us," I said, "Somewhere down the line."

"I suppose that's true," she said, and inevitably my thoughts turned to the pending presidential election, to the founding premise of this great nation that so many seem to have forgotten.

"She was so lovely," one woman said, of my Chinese grandmother. "She looks very young."

"Fourteen or so when she had her first child," I said.

"That's how it was back then," the woman said. We shared a look. "I hope it was what she wanted. The photos don't tell us that part of the story, do they?" We shared another look.

I would launch into my spiel when anyone paused at my table. "It's a book about my father, an art teacher. It's about his art," I would say. And some, more than I ever expected, would linger and pick up the book. They would accept one of the art cards or a bookmark, perhaps only a piece of candy.

"It's a beautiful thing you've done. A beautiful tribute. He would be proud," one woman said.

"I guess I have to buy the book to find out why he was 'the reluctant artist'," one older man said, winking at me as he followed his wife from table to table. "I guess everybody's got an angle," he called back over his shoulder.

I did sell a handful of books. But it's the conversations I will remember. The expressions on people's faces. The connections with their own past, the journeys of their parents and grandparents. They responded as teachers, artists, would-be artists and art lovers, as children and grandchildren, as immigrants and children of immigrants.

"Your father was a hapa haole," one man said, with a big smile of recognition. "Like my grandchildren. They're half white."

"Mine too," I said.

By the time I made it back to the concession table, there was nothing but a few dried-out donuts left. I'd waited too long. The coconut, chocolate and butterscotch-chip dream bars I'd coveted were gone. I suppose it's just as well.

It was six hours of a Saturday that I had expected would seem interminable and leave me drained and wondering why I'd bothered. Instead, the time passed quickly. I was left with a sense of gratitude. I had been reminded of something important. What this odd-ball book, this "art book/memoir" that doesn't fit neatly on any bookstore shelf, that doesn't have some easily explained niche or audience, is about.

Art

Family

Heritage

Respect

Honoring one man's legacy

Creating a record, a repository

Putting it out there

So many things

I shouldn't need to be reminded of

But sometimes I do

For related posts, visit my author blog, here.

Dozens were drawn in by the photograph of my father's family. The one where he's an infant, seated on his mother's lap.

"That could be my family," one woman said, with a wistful smile.

There were questions about his heritage. About how his Hungarian soldier father and Chinese mother met.

"So many of us come from somewhere else, don't we?" one woman said.

"Almost all of us," I said, "Somewhere down the line."

"I suppose that's true," she said, and inevitably my thoughts turned to the pending presidential election, to the founding premise of this great nation that so many seem to have forgotten.

"She was so lovely," one woman said, of my Chinese grandmother. "She looks very young."

"Fourteen or so when she had her first child," I said.

"That's how it was back then," the woman said. We shared a look. "I hope it was what she wanted. The photos don't tell us that part of the story, do they?" We shared another look.

I would launch into my spiel when anyone paused at my table. "It's a book about my father, an art teacher. It's about his art," I would say. And some, more than I ever expected, would linger and pick up the book. They would accept one of the art cards or a bookmark, perhaps only a piece of candy.

"It's a beautiful thing you've done. A beautiful tribute. He would be proud," one woman said.

"I guess I have to buy the book to find out why he was 'the reluctant artist'," one older man said, winking at me as he followed his wife from table to table. "I guess everybody's got an angle," he called back over his shoulder.

I did sell a handful of books. But it's the conversations I will remember. The expressions on people's faces. The connections with their own past, the journeys of their parents and grandparents. They responded as teachers, artists, would-be artists and art lovers, as children and grandchildren, as immigrants and children of immigrants.

"Your father was a hapa haole," one man said, with a big smile of recognition. "Like my grandchildren. They're half white."

"Mine too," I said.

By the time I made it back to the concession table, there was nothing but a few dried-out donuts left. I'd waited too long. The coconut, chocolate and butterscotch-chip dream bars I'd coveted were gone. I suppose it's just as well.

It was six hours of a Saturday that I had expected would seem interminable and leave me drained and wondering why I'd bothered. Instead, the time passed quickly. I was left with a sense of gratitude. I had been reminded of something important. What this odd-ball book, this "art book/memoir" that doesn't fit neatly on any bookstore shelf, that doesn't have some easily explained niche or audience, is about.

Art

Family

Heritage

Respect

Honoring one man's legacy

Creating a record, a repository

Putting it out there

So many things

I shouldn't need to be reminded of

But sometimes I do

For related posts, visit my author blog, here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed