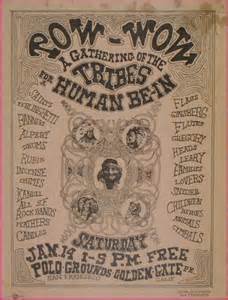

My sister Roxanne and her best friend were at the historic 1967 Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, an event staged to protest a new California law banning LSD. There was free entertainment: Jefferson Airplane, Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Quicksilver Messenger Service, and others. Owsley Stanley distributed his special LSD.

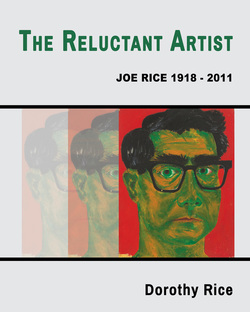

Excerpted from The Reluctant Artist, continued below . . .

Walking away from the event, my sister recalls that a repurposed school bus slowed down alongside them. The driver leaned out and asked if she and her friend wanted a ride. Without giving it much thought — you didn’t give casual invitations much thought back then — they got in and joined several children

and adults in the back. The driver was an older guy. Once inside Roxanne was disappointed that he wasn’t cuter.

The massive gathering in Golden Gate Park led the six o’clock news.

That night, long after dark, I overheard Dad talking to her on the phone. His voice shook with suppressed anger, and he muttered, “Jesus H. Christ,” under his breath, never a good thing. After Dad stomped down the basement stairs to the car and drove up the driveway, I stayed awake for what felt like hours, waiting for him to bring my sister home. Finally, she tiptoed into our bedroom and shut the door.

She whispered across the divide between our twin beds, her face illumined by the moonlight through our gauzy bedroom curtains. “I knew it was bad when this hippie bus crossed the bridge. This guy, Ken something, drove clear to this house in Larkspur. He said it was his lawyer’s. They were all talking about leaving for Oregon in the morning, and they acted like Evelyn and I were along for the ride. Nobody even asked.”

“So what happened?” I clutched the blankets and imagined an orgy.

“Absolutely nothing. They acted normal. Someone went out for Kentucky Fried Chicken. I mean, really. KFC. They’re just hanging out. Eating fried chicken. So I get up my nerve and I tell this Ken dude that we can’t go to Oregon, that I have school on Monday. They all cracked up like we were idiots.”

The lump of her body beneath a pale chenille bedspread shook with suppressed laughter.

and adults in the back. The driver was an older guy. Once inside Roxanne was disappointed that he wasn’t cuter.

The massive gathering in Golden Gate Park led the six o’clock news.

That night, long after dark, I overheard Dad talking to her on the phone. His voice shook with suppressed anger, and he muttered, “Jesus H. Christ,” under his breath, never a good thing. After Dad stomped down the basement stairs to the car and drove up the driveway, I stayed awake for what felt like hours, waiting for him to bring my sister home. Finally, she tiptoed into our bedroom and shut the door.

She whispered across the divide between our twin beds, her face illumined by the moonlight through our gauzy bedroom curtains. “I knew it was bad when this hippie bus crossed the bridge. This guy, Ken something, drove clear to this house in Larkspur. He said it was his lawyer’s. They were all talking about leaving for Oregon in the morning, and they acted like Evelyn and I were along for the ride. Nobody even asked.”

“So what happened?” I clutched the blankets and imagined an orgy.

“Absolutely nothing. They acted normal. Someone went out for Kentucky Fried Chicken. I mean, really. KFC. They’re just hanging out. Eating fried chicken. So I get up my nerve and I tell this Ken dude that we can’t go to Oregon, that I have school on Monday. They all cracked up like we were idiots.”

The lump of her body beneath a pale chenille bedspread shook with suppressed laughter.

“Dad was so pissed when I called. You know how he gets. But I had no choice. I want to graduate high school, right? So all the time we’re waiting for him,” Roxanne said, “I’m scared to death. I’m thinking it’s going to be the silent treatment for the rest of my life.”

Curled up under the covers, I hugged my bent knees and pretended to myself that I would have stayed on the bus and gone to that commune in Oregon.

“So the strangest thing,” Roxanne said, resuming her story, “I hear voices at the door. I go see who it is and it’s Dad. But it was so weird. He’s smiling and all chatty, like they’re old friends or something.”

“Chatty?” I said, interrupting her. “Chatty?”

“I know,” she said. “I practically didn’t recognize him.”

It was Ken Kesey (author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) driving that bus, with some of the Merry Pranksters as passengers. From looking at old photographs on the internet, Roxanne now thinks Neal Cassady and Mountain Girl were among them. Our father had known Kesey and the painted school bus in the driveway instantly. With something akin to awe, he told Roxanne she’d be relating the story to her own children one day.

My sister remembers Dad was disgusted with her for not knowing who Ken Kesey was, and that her ignorance seemed to anger him more than what she’d done.

I imagine our father’s rueful sigh, the resigned shrug of his shoulders. “Life is wasted on the young,” he might have said. And if he didn’t, he likely thought it. For whatever else Kesey might have been, facing drug charges, crisscrossing the country in an old school bus, acquiring sycophants along the way, our father admired him as an author, a thinker, a man who was already iconic of the times.

Recalling the incident, my sister and I wondered if he wouldn’t have been secretly pleased if she had stayed on the bus and had the experience of a lifetime.

My father had a grudging admiration for artists who put their own passions and drives above all else. At times, I believe he resented the restrictions of being a husband and father. Yet he had a strong sense of ethical obligation and propriety. I wonder what his life would have been without us.

Excerpted from The Reluctant Artist, 40% off through December, Discount Code: HOLIDAY40

Curled up under the covers, I hugged my bent knees and pretended to myself that I would have stayed on the bus and gone to that commune in Oregon.

“So the strangest thing,” Roxanne said, resuming her story, “I hear voices at the door. I go see who it is and it’s Dad. But it was so weird. He’s smiling and all chatty, like they’re old friends or something.”

“Chatty?” I said, interrupting her. “Chatty?”

“I know,” she said. “I practically didn’t recognize him.”

It was Ken Kesey (author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest) driving that bus, with some of the Merry Pranksters as passengers. From looking at old photographs on the internet, Roxanne now thinks Neal Cassady and Mountain Girl were among them. Our father had known Kesey and the painted school bus in the driveway instantly. With something akin to awe, he told Roxanne she’d be relating the story to her own children one day.

My sister remembers Dad was disgusted with her for not knowing who Ken Kesey was, and that her ignorance seemed to anger him more than what she’d done.

I imagine our father’s rueful sigh, the resigned shrug of his shoulders. “Life is wasted on the young,” he might have said. And if he didn’t, he likely thought it. For whatever else Kesey might have been, facing drug charges, crisscrossing the country in an old school bus, acquiring sycophants along the way, our father admired him as an author, a thinker, a man who was already iconic of the times.

Recalling the incident, my sister and I wondered if he wouldn’t have been secretly pleased if she had stayed on the bus and had the experience of a lifetime.

My father had a grudging admiration for artists who put their own passions and drives above all else. At times, I believe he resented the restrictions of being a husband and father. Yet he had a strong sense of ethical obligation and propriety. I wonder what his life would have been without us.

Excerpted from The Reluctant Artist, 40% off through December, Discount Code: HOLIDAY40

RSS Feed

RSS Feed