Literary Arts and Wine, Poetry & Prose in Truckee, CA

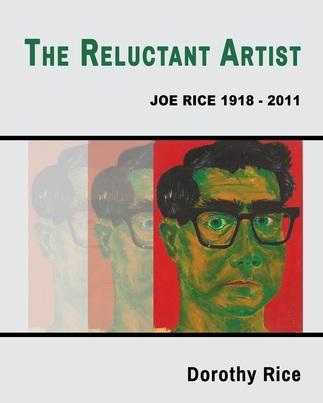

September Reading/Slide Show at Art Truckee

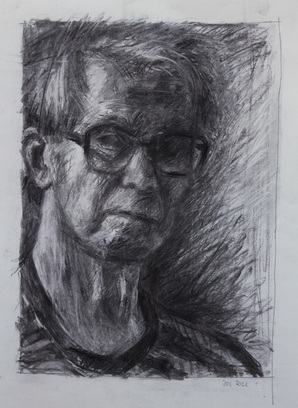

Dorothy will read from The Reluctant Artist, her book about Joe Rice and his art. The reading will include a slide show featuring many of the book's gorgeous illustrations, which span the artist's creative life, beginning with jewelry crafted in the 50s and sold on Berkeley's Telegraph Avenue, moving through bold geometric and surrealistic paintings created in the 60s and 70s and ending with Rice's work from his final productive decades of the 80s and 90s, softer, more impressionistic subjects and treatments, as well as dozens of whimsical ceramic pieces.

Here is just a brief sample of some of the work featured in the book and the slide show. Enjoy.

September Reading/Slide Show at Art Truckee

- Sunday, September 18, 2016

- 6:00pm 7:00pm

- Art Truckee, 10072 Donner Pass Road, Truckee, CA

Dorothy will read from The Reluctant Artist, her book about Joe Rice and his art. The reading will include a slide show featuring many of the book's gorgeous illustrations, which span the artist's creative life, beginning with jewelry crafted in the 50s and sold on Berkeley's Telegraph Avenue, moving through bold geometric and surrealistic paintings created in the 60s and 70s and ending with Rice's work from his final productive decades of the 80s and 90s, softer, more impressionistic subjects and treatments, as well as dozens of whimsical ceramic pieces.

Here is just a brief sample of some of the work featured in the book and the slide show. Enjoy.

And here is the segment that I will begin the reading with, from the book's opening pages:

The Reluctant Artist

My father was an artist, a prolific and skillful painter, sculptor, jewelry maker, and craftsman who continued to produce work into his eighties. He sought no recognition or acknowledgment for his efforts, and he never made a living at it. The closest he came to trying was during the 1950s when he attempted to sell his jewelry on what is now Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue.

“We could have used the money,” my mother said,with a grudging laugh that has stuck with her for over fifty years, “but your father was never much of a salesman.”

No surprise there. I imagine him sitting with his back to a wall, legs crossed at the ankle, nose in a textbook, a forelock of black hair covering his eyes, while students and bohemian riffraff paused to admire his jewelry — silver and wood necklaces, pendants, and earrings scattered on a rumpled bed sheet. A blonde beatnik chick in a black turtleneck sweater, sipping espresso from a nearby café, might have plucked an earring from the sheet and dangled it beside her ear, while her bearded companion, in heated intellectual debate with a newfound acquaintance, gesticulated and sputtered to make his point. Oblivious, my father turned the page in his book.

“I think he just wanted out of the house,” my mother added.

Which seems reasonable. The last of their four children was born in 1958 into a cramped two-bedroom row house in San Francisco’s Sunset District, three girls in one bedroom, our brother in the other, Mom and Dad on a roll-out couch in the living room.

I once sat beside my father on that couch. It spanned the length of the big bay window that looked out onto 45th Avenue. I would have been around six, for my knees didn’t quite reach the edge of the cushion. My stocking feet jutted out stiffly before me. From the zoo,only two blocks away,the manic whoops of spider monkeys on Monkey Island and the lions’ echoing roar at feeding time found their way into our living room.

“And who’s this?” Dad asked, turning another page in the coffee table book on his lap.

“Van Gogh,” I said.

“What makes you say that?”

I traced a whorl in the black and blue night sky with a fingertip and watched my father’s face.

He didn’t look at me, but I detected the hint of a smile. I imagined I’d got the right answer without him saying so. Dad turned the page to a painting of two dark-skinned women with bare breasts.

“And this one?”

I bounced my legs against the cushion.

“Gauguin,” he said, when I didn’t answer. “Another crazed Frenchman.”

“But not so crazy,” I said. The women had a serene, seductive beauty. Not that I thought in those terms at six or seven, but perhaps I intuited the paradisaical calm of the place from their sloe eyes and languid arms. There were no frantic, trapped circles, no angry daubs of paint.

“Indeed,” he said. “Not nearly so crazy. Not so nice either, by all accounts. Van Gogh had an excuse. Poor wretch.”

I liked Van Gogh all the more for being crazy, and for long ago creating images of such singular beauty that my father revered them with a quiet conviction that was almost a religion.

My father’s lifelong relationship with art was a constant in our lives, from the books on our shelves, the museums we visited, and the topics of conversation at our dinner table. Proof of his quiet labor graced our surroundings — paintings on the walls, Mother’s fancy, going-out earrings, her pearl and silver ring, the marble-topped coffee table that sat in front of the couch when it wasn’t a bed, a lamp constructed from a turquoise ceramic pot. His facility for creation was rarely spoken of. It just was.

an excerpt from The Reluctant Artist, by Dorothy Rice

The Reluctant Artist

My father was an artist, a prolific and skillful painter, sculptor, jewelry maker, and craftsman who continued to produce work into his eighties. He sought no recognition or acknowledgment for his efforts, and he never made a living at it. The closest he came to trying was during the 1950s when he attempted to sell his jewelry on what is now Berkeley’s Telegraph Avenue.

“We could have used the money,” my mother said,with a grudging laugh that has stuck with her for over fifty years, “but your father was never much of a salesman.”

No surprise there. I imagine him sitting with his back to a wall, legs crossed at the ankle, nose in a textbook, a forelock of black hair covering his eyes, while students and bohemian riffraff paused to admire his jewelry — silver and wood necklaces, pendants, and earrings scattered on a rumpled bed sheet. A blonde beatnik chick in a black turtleneck sweater, sipping espresso from a nearby café, might have plucked an earring from the sheet and dangled it beside her ear, while her bearded companion, in heated intellectual debate with a newfound acquaintance, gesticulated and sputtered to make his point. Oblivious, my father turned the page in his book.

“I think he just wanted out of the house,” my mother added.

Which seems reasonable. The last of their four children was born in 1958 into a cramped two-bedroom row house in San Francisco’s Sunset District, three girls in one bedroom, our brother in the other, Mom and Dad on a roll-out couch in the living room.

I once sat beside my father on that couch. It spanned the length of the big bay window that looked out onto 45th Avenue. I would have been around six, for my knees didn’t quite reach the edge of the cushion. My stocking feet jutted out stiffly before me. From the zoo,only two blocks away,the manic whoops of spider monkeys on Monkey Island and the lions’ echoing roar at feeding time found their way into our living room.

“And who’s this?” Dad asked, turning another page in the coffee table book on his lap.

“Van Gogh,” I said.

“What makes you say that?”

I traced a whorl in the black and blue night sky with a fingertip and watched my father’s face.

He didn’t look at me, but I detected the hint of a smile. I imagined I’d got the right answer without him saying so. Dad turned the page to a painting of two dark-skinned women with bare breasts.

“And this one?”

I bounced my legs against the cushion.

“Gauguin,” he said, when I didn’t answer. “Another crazed Frenchman.”

“But not so crazy,” I said. The women had a serene, seductive beauty. Not that I thought in those terms at six or seven, but perhaps I intuited the paradisaical calm of the place from their sloe eyes and languid arms. There were no frantic, trapped circles, no angry daubs of paint.

“Indeed,” he said. “Not nearly so crazy. Not so nice either, by all accounts. Van Gogh had an excuse. Poor wretch.”

I liked Van Gogh all the more for being crazy, and for long ago creating images of such singular beauty that my father revered them with a quiet conviction that was almost a religion.

My father’s lifelong relationship with art was a constant in our lives, from the books on our shelves, the museums we visited, and the topics of conversation at our dinner table. Proof of his quiet labor graced our surroundings — paintings on the walls, Mother’s fancy, going-out earrings, her pearl and silver ring, the marble-topped coffee table that sat in front of the couch when it wasn’t a bed, a lamp constructed from a turquoise ceramic pot. His facility for creation was rarely spoken of. It just was.

an excerpt from The Reluctant Artist, by Dorothy Rice

RSS Feed

RSS Feed