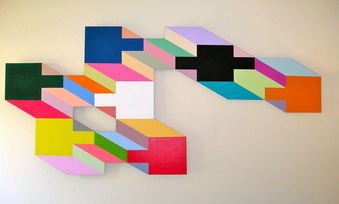

Hard-edge painting is a tendency in late 1950s and 1960s art that is closely related to Post-painterly abstraction and Color Field Painting. It describes an abstract style that combines the clear composition of geometric abstraction with the intense color and bold, unitary forms of color field painting. Although it was first identified with Californian artists, today the phrase is used to describe one of the most distinctive tendencies in abstract painting throughout the United States in the 1960s. |

When I was a teenager in the 60s and early 70s my father created most of the paintings I love most and that seemed to me to most reflect who he was as an artist, or, at least, the artist I wanted him to be.

Many years later I learned there was a name for what he was doing back then. Hard-edge, as exemplified by the work of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, who died recently at 92. Attribution of the term "hard-edge abstraction" is given to California art critic Jules Langsner in connection with a 1959 exhibition of four West Coast artists, Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley and Lorser Feitelson, artists who became associated with "California hard-edge." On seeing Dad's work for the first time some people say it reminds them of Frank Stella and also Kenneth Noland.

While I didn't know my father was painting hard-edge, I am fairly certain he did, for he was taking classes at the San Francisco Art Institute at the time, and he subscribed to several arts magazines that littered our coffee table.

It wasn't until I began to catalog his work in the 2000s, taking photographs and building an online archive, that I also began to pay closer attention to the broader context for my father's art.

Many years later I learned there was a name for what he was doing back then. Hard-edge, as exemplified by the work of artists such as Ellsworth Kelly, who died recently at 92. Attribution of the term "hard-edge abstraction" is given to California art critic Jules Langsner in connection with a 1959 exhibition of four West Coast artists, Karl Benjamin, John McLaughlin, Frederick Hammersley and Lorser Feitelson, artists who became associated with "California hard-edge." On seeing Dad's work for the first time some people say it reminds them of Frank Stella and also Kenneth Noland.

While I didn't know my father was painting hard-edge, I am fairly certain he did, for he was taking classes at the San Francisco Art Institute at the time, and he subscribed to several arts magazines that littered our coffee table.

It wasn't until I began to catalog his work in the 2000s, taking photographs and building an online archive, that I also began to pay closer attention to the broader context for my father's art.

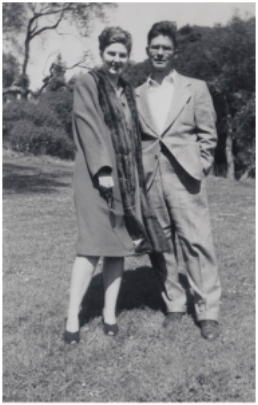

Joe Rice, 1970s

Joe Rice, 1970s I recall one afternoon at his Sonoma house. This was in the last few years of his life. I sought to draw him out, to get him talking about art. I asked what he thought of other hard-edge painters.

He squinted at my use of the term, with what I took as suspicion. I felt as if I'd been snooping into matters that were his personal business and none of mine.

I then dropped a few names, Stella, Noland, and others, showing off my newfound knowledge and hoping for some reaction.

My father glared at me, nonplussed.

Oh, I suppose I was influenced by Piet Mondrian, he said with a tired sigh, referencing the Dutch painter (1872-1944).

I asked why he'd stopped painting that way, trying not to appear too obvious about my preference for his hard-edge work over all the looser abstractions and more representational subjects that followed in the 80s and 90s.

It was exacting to paint like that, my father said, every line just so. I suppose I got less precise with age, by necessity perhaps, more impressionistic. He flexed his stiff hands, the knuckles thick with arthritis.

Soft-edge, I said.

He met my gaze. His chin dipped and he gave me a tight smile in acknowledgment of my small pun.

Indeed, he said, soft-edge.

He squinted at my use of the term, with what I took as suspicion. I felt as if I'd been snooping into matters that were his personal business and none of mine.

I then dropped a few names, Stella, Noland, and others, showing off my newfound knowledge and hoping for some reaction.

My father glared at me, nonplussed.

Oh, I suppose I was influenced by Piet Mondrian, he said with a tired sigh, referencing the Dutch painter (1872-1944).

I asked why he'd stopped painting that way, trying not to appear too obvious about my preference for his hard-edge work over all the looser abstractions and more representational subjects that followed in the 80s and 90s.

It was exacting to paint like that, my father said, every line just so. I suppose I got less precise with age, by necessity perhaps, more impressionistic. He flexed his stiff hands, the knuckles thick with arthritis.

Soft-edge, I said.

He met my gaze. His chin dipped and he gave me a tight smile in acknowledgment of my small pun.

Indeed, he said, soft-edge.

June Rice and daughters, 2015

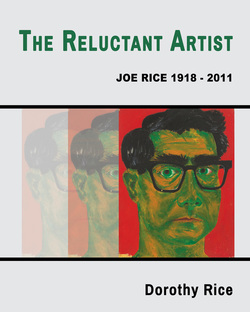

June Rice and daughters, 2015 Christmas 2015, my sisters and I visited our 93 year old mother at the memory care facility where she has lived the past several years. I'd brought her a copy of my book about Dad and his art and set it on the coffee table in her tiny apartment. She picked it up and considered it with a furrowed brow.

I didn't know anyone had done something like this, she said, with a lilt in her voice that sounded both pleased and surprised.

I did, I said, I put it together.

Well that's nice, she said, turning to me. By her blank stare and polite smile I imagined she had no idea who I was.

The Reluctant Artist, she said, holding the book out in front of her and reading from the cover. It's the perfect title. Boy, if he was anything, he was that alright, reluctant, and not only about art.

Their's was never an easy marriage. Mother was a romantic and father a pragmatic man of few words who spent most of his leisure hours closeted in the basement, painting. They were married over forty years and had four children together and while they divorced in the 80s and father remarried, they remained friends, with what always seemed to me a grudging respect for one another.

Mother turned the pages of the book. My sister guided her to the photographs of father's paintings and ceramics at the back.

I never got this stuff, mother said, crinkling her nose with distaste at a photo of one of his hard-edge paintings. So cold and unfeeling. I always wondered what that was all about.

Mother didn't think to change out of her nightgown for the fancy Christmas feast in the dining room that afternoon but she'd known Dad's image instantly, the green self-portrait on the cover of my book. And in finding meaning and resonance in the title, she had given me the greatest possible accolade.

I'd gotten something right.

I didn't know anyone had done something like this, she said, with a lilt in her voice that sounded both pleased and surprised.

I did, I said, I put it together.

Well that's nice, she said, turning to me. By her blank stare and polite smile I imagined she had no idea who I was.

The Reluctant Artist, she said, holding the book out in front of her and reading from the cover. It's the perfect title. Boy, if he was anything, he was that alright, reluctant, and not only about art.

Their's was never an easy marriage. Mother was a romantic and father a pragmatic man of few words who spent most of his leisure hours closeted in the basement, painting. They were married over forty years and had four children together and while they divorced in the 80s and father remarried, they remained friends, with what always seemed to me a grudging respect for one another.

Mother turned the pages of the book. My sister guided her to the photographs of father's paintings and ceramics at the back.

I never got this stuff, mother said, crinkling her nose with distaste at a photo of one of his hard-edge paintings. So cold and unfeeling. I always wondered what that was all about.

Mother didn't think to change out of her nightgown for the fancy Christmas feast in the dining room that afternoon but she'd known Dad's image instantly, the green self-portrait on the cover of my book. And in finding meaning and resonance in the title, she had given me the greatest possible accolade.

I'd gotten something right.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed