In the 1960s, San Francisco’s Sunset District where I grew up, two blocks from the zoo, three from Ocean Beach, was prime trick-or-treating territory. Row houses for miles in an even grid, four blocks to a mile, or so my father used to say. On a good Halloween night, with the right weather and a posse of single-minded friends, you could cover an area several miles squared, from the spooky flat-faced stucco houses fronting the Great Highway, clear up to the wooded median strip at Sunset Boulevard.

Pillowcases slung over our shoulders like Santa Claus we jogged to the furthest point of our planned route then worked our way back down, a determined trot from house to house, up to the door, hold out the sack, then back to the sidewalk, no time to assess the loot or pause for idle chit chat, the goal a bag so heavy-laden, so lumpy and distended, you could scarcely manage to drag it home at evening’s end.

We would dump our take on the living room floor, my sisters and I careful to maintain the boundaries between our three piles. We categorized, kept meticulous count and swapped for favorites. Mom maintained a watchful eye over the proceedings; she confiscated the homemade popcorn balls in saran wrap, the wax paper bags of cookies and any other suspicious-looking items. She said it was for our safety, just in case.

Despite how impressive my haul had seemed on Halloween night, it was all gone in a matter of weeks, while my older sister’s lasted well past Christmas. She might toss me a stale piece of taffy now and then, hard enough to crack a tooth. But she hung onto the good stuff, chocolate candy bars and all-day suckers, to slowly savor in my presence.

“Your sister doesn’t have to share,” Mother would say. “She saved hers. You didn’t.”

It was a mystery how quickly my candy disappeared. I never remembered eating that much. It wasn’t until I became a mother and inevitably found myself raiding my children’s candy stashes, that the likely truth dawned. My older sister must have had better hiding spots.

Pillowcases slung over our shoulders like Santa Claus we jogged to the furthest point of our planned route then worked our way back down, a determined trot from house to house, up to the door, hold out the sack, then back to the sidewalk, no time to assess the loot or pause for idle chit chat, the goal a bag so heavy-laden, so lumpy and distended, you could scarcely manage to drag it home at evening’s end.

We would dump our take on the living room floor, my sisters and I careful to maintain the boundaries between our three piles. We categorized, kept meticulous count and swapped for favorites. Mom maintained a watchful eye over the proceedings; she confiscated the homemade popcorn balls in saran wrap, the wax paper bags of cookies and any other suspicious-looking items. She said it was for our safety, just in case.

Despite how impressive my haul had seemed on Halloween night, it was all gone in a matter of weeks, while my older sister’s lasted well past Christmas. She might toss me a stale piece of taffy now and then, hard enough to crack a tooth. But she hung onto the good stuff, chocolate candy bars and all-day suckers, to slowly savor in my presence.

“Your sister doesn’t have to share,” Mother would say. “She saved hers. You didn’t.”

It was a mystery how quickly my candy disappeared. I never remembered eating that much. It wasn’t until I became a mother and inevitably found myself raiding my children’s candy stashes, that the likely truth dawned. My older sister must have had better hiding spots.

Mother’s Vacation

Dessert was a spoonful of sweetened condensed milk

the summer our mother went away.

Father served it up with grim determination

like administering castor oil.

My sisters and I - four, eight and twelve -

stood on tiptoe by the refrigerator’s light,

jostling for our rightful share.

We slid on the hardwood floor in stocking feet.

We whispered while we braided his long black hair.

Father pretended not to notice, or slept,

his mouth a curved line we hoped was a smile.

Until past sundown we roamed the streets like boys

from the Great Highway to Sunset Boulevard, the zoo to Taraval.

Four blocks make a city mile.

He made us soft-boiled eggs and toast,

sent us off with sack lunches, towels and a nickel.

To the world’s largest outdoor swimming pool

where my big sister flirted with boys in her new two-piece.

I held my little sister’s hand.

We stared over the concrete lip into the murky salt water

where baby sharks and sucking sand dunes lurked.

At night he told us stories, of being a boy in the Philippines,

catching pythons with a pig inside a cage, running through the rice.

Our three names fell from father’s lips, like a song and

dessert was a spoonful of sweetened condensed milk

that first summer our mother went away.

Dessert was a spoonful of sweetened condensed milk

the summer our mother went away.

Father served it up with grim determination

like administering castor oil.

My sisters and I - four, eight and twelve -

stood on tiptoe by the refrigerator’s light,

jostling for our rightful share.

We slid on the hardwood floor in stocking feet.

We whispered while we braided his long black hair.

Father pretended not to notice, or slept,

his mouth a curved line we hoped was a smile.

Until past sundown we roamed the streets like boys

from the Great Highway to Sunset Boulevard, the zoo to Taraval.

Four blocks make a city mile.

He made us soft-boiled eggs and toast,

sent us off with sack lunches, towels and a nickel.

To the world’s largest outdoor swimming pool

where my big sister flirted with boys in her new two-piece.

I held my little sister’s hand.

We stared over the concrete lip into the murky salt water

where baby sharks and sucking sand dunes lurked.

At night he told us stories, of being a boy in the Philippines,

catching pythons with a pig inside a cage, running through the rice.

Our three names fell from father’s lips, like a song and

dessert was a spoonful of sweetened condensed milk

that first summer our mother went away.

I believed he had each of his daughters slotted from an early age, that he had assigned us roles. We grew up hemmed within the constraints of those roles. Roxanne was good-natured, no great student but genial as a “great galumphing Saint Bernard,” as my father once said. Younger sister Juliet, with her violet eyes and long dark hair, was the beautiful one, a rival to Romeo’s fair Juliet. I assumed the role of the resentful ugly duckling, the prickly one, quick to take offence.

I don’t know how much of that actually came from him. I inserted my own fears and insecurities into his silences, his cryptic observations and bemused expressions. I chose to interpret every word, every shrug, as personal. What is true, I think, is that none of us really knew what he thought, whether he was proud or pleased with the children we were and the adults we became. I don’t know that having four children — our brother, also Joe Rice, is the eldest — was anything he ever wanted or counted among his accomplishments, if he even kept track of such things. Which is not to say he wasn’t a good father and that he didn’t give us many of the things that matter most. He did.

Quiet things. Small things.

He built a playhouse for us under the big tree in the backyard. He constructed Halloween costumes for us that were like no one else’s. I was a can of orange soda one year: a sturdy, cardboard cylinder, painted to Pop art perfection, hung from my shoulders to below my knees. Another year I was a bumblebee with handcrafted gossamer wings. He taught me to peel an orange in one continuous curling ribbon, a skill that brings me pleasure to this day. He replicated one of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machines out of toothpicks for my fifth grade report on the Renaissance. He let us walk beside him to the hardware store or along the beach, his stride loose and relaxed, arms swinging, offering the occasional oblique smile or observation. On Sunday nights, before we got our first television, I watched Bonanza at the Jensen’s down the block; my father was always there on the sidewalk at eight o’clock, waiting to see me safely home. He slipped Roxanne dimes for a frozen juice bar or a fudgsicle from the school cafeteria. It was their secret. In different ways, at different times, he allowed each of us to imagine that we were connected, that we had an understanding, that we saw things alike.

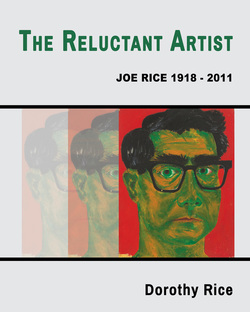

Excerpt from The Reluctant Artist: Joe Rice 1918 - 2011

I don’t know how much of that actually came from him. I inserted my own fears and insecurities into his silences, his cryptic observations and bemused expressions. I chose to interpret every word, every shrug, as personal. What is true, I think, is that none of us really knew what he thought, whether he was proud or pleased with the children we were and the adults we became. I don’t know that having four children — our brother, also Joe Rice, is the eldest — was anything he ever wanted or counted among his accomplishments, if he even kept track of such things. Which is not to say he wasn’t a good father and that he didn’t give us many of the things that matter most. He did.

Quiet things. Small things.

He built a playhouse for us under the big tree in the backyard. He constructed Halloween costumes for us that were like no one else’s. I was a can of orange soda one year: a sturdy, cardboard cylinder, painted to Pop art perfection, hung from my shoulders to below my knees. Another year I was a bumblebee with handcrafted gossamer wings. He taught me to peel an orange in one continuous curling ribbon, a skill that brings me pleasure to this day. He replicated one of Leonardo da Vinci’s flying machines out of toothpicks for my fifth grade report on the Renaissance. He let us walk beside him to the hardware store or along the beach, his stride loose and relaxed, arms swinging, offering the occasional oblique smile or observation. On Sunday nights, before we got our first television, I watched Bonanza at the Jensen’s down the block; my father was always there on the sidewalk at eight o’clock, waiting to see me safely home. He slipped Roxanne dimes for a frozen juice bar or a fudgsicle from the school cafeteria. It was their secret. In different ways, at different times, he allowed each of us to imagine that we were connected, that we had an understanding, that we saw things alike.

Excerpt from The Reluctant Artist: Joe Rice 1918 - 2011

RSS Feed

RSS Feed